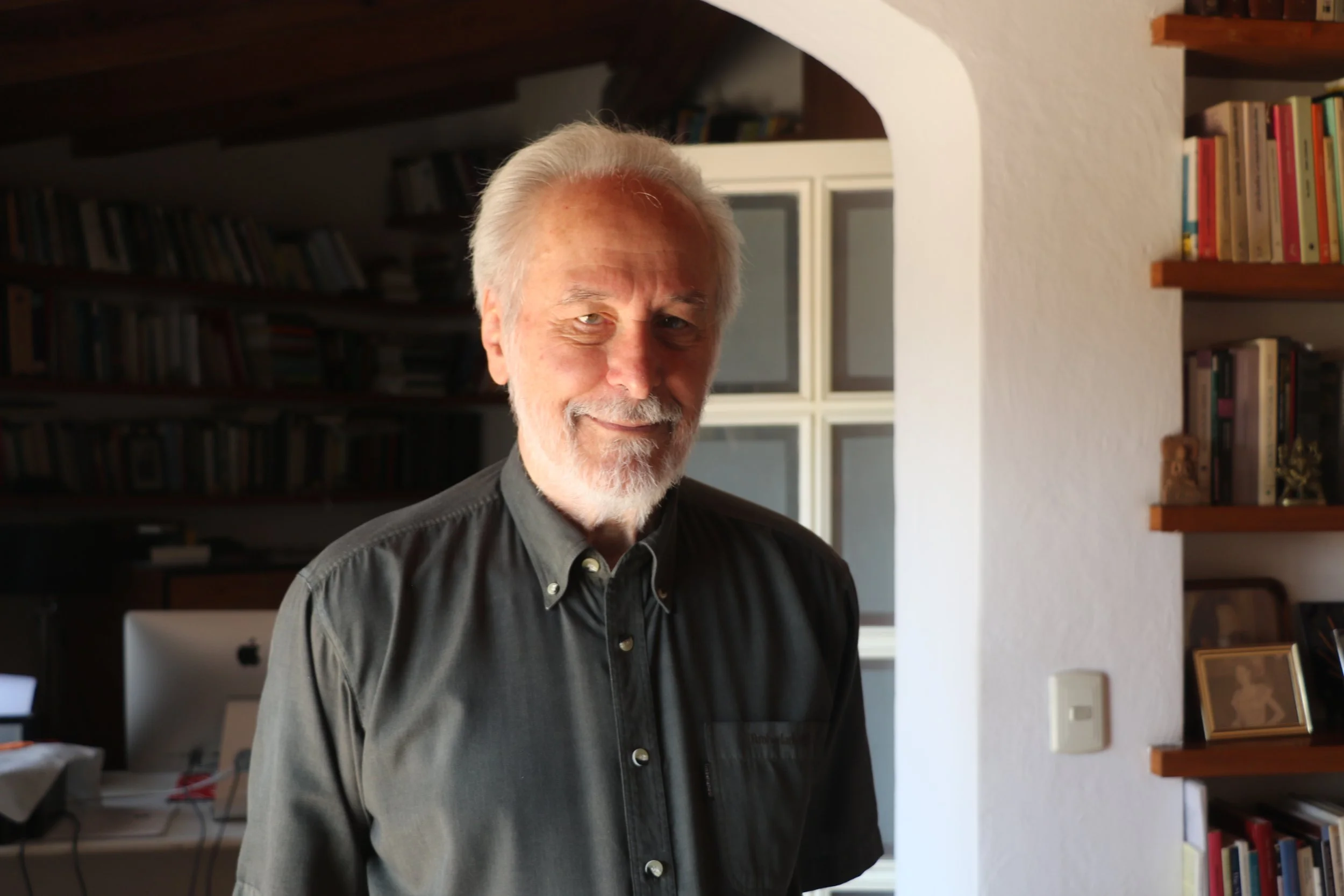

José Luis Díaz Gómez

Mi camino une la ciencia con la enseñanza, la investigación con la curiosidad. A lo largo de los años he compartido conocimiento, dirigido proyectos, y aportado ideas que buscan entender mejor nuestro entorno.

Trayectoria

-

Primaria: Instituto Fray Juan de Zumárraga, México, D.F. (1948-1953).

Secundaria (1-4 Bachillerato): Colegio de Cristo Rey, La Coruña, España (1954-1957).

Preparatoria: Centro Universitario México, México, D.F. (1958-1959).

Licenciatura: Facultad Nacional de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). México, D.F. (1960-1966).

Internado rotatorio, Hospital Español de México, México, D.F. 1965.

Servicio Social en Psiquiatría Clínica. Hospital Granja “La Salud Tlazolteotl”, S.S.A. Zoquiapan, Edo de México, 1966.

Título de Médico Cirujano: 9 de febrero de 1967.

FORMACIÓN COMPLEMENTARIA

Noviembre 1961 a febrero 1962. Externado rotatorio en Medicina General, Tucson Medical Center, Tucson, Arizona, E.U.A.

Noviembre 1962 a febrero 1963. Externado rotatorio en Medicina General, Tucson Medical Center, Tucson, Arizona, E.U.A

1962-1963. Curso de prosector en Anatomía Patológica (Impartido por Dr. Ruy Pérez Tamayo). Hospital General de México, S.S.A., México, D.F.

1964-1965. Cursos y práctica en Neuropsiquiatría clínica (Impartidos por Dr. Dionisio Nieto) Pabellón Piloto del Manicomio General “La Castañeda”, S.S.A. México, D.F.

1967-1968. Pre requisitos, Cursos y trabajo de investigación del doctorado en Bioquímica (Dr. Guillermo Soberón). Facultad de Medicina e Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, UNAM, México, D.F.

1968-1970. Investigación bajo la supervisión del Dr. Dionisio Nieto en el Departamento de Neurobiología, Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas UNAM y del Dr. Carlos Guzmán Flores en la Unidad de Investigaciones Cerebrales del Instituto Nacional de Neurología.

Junio 1970 a junio 1972. Investigador asociado. Psychiatric Research Laboratories, Harvard Medical School y Massachusetts General Hospital (Laboratorio y dirección de Seymour S. Kety), Boston, Massachusetts, E.U.A.

-

Investigador titular “C” de tiempo completo.

Departamento de Historia y Filosofía de la Medicina, Facultad de Medicina.

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.

Dirección: Brasil 33 y Venezuela, Centro Histórico, México D.F.

Tel: 5526-2297, 5526-3853.

Antigüedad como investigador de la UNAM: desde mayo, 1967.

-

Profesor y tutor. Maestría y Doctorado en Filosofía de la Ciencia: Filosofía de las Ciencias Cognitivas. Facultad de Filosofía y Letras e Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas, UNAM. México. D.F. Desde 2005. Curso vigente: Neurociencia cognitiva, las facultades mentales.

Profesor y tutor. Maestría y Doctorado en Neurobiología, Instituto de Neurobiología, UNAM México, D.F. Desde 1997.

Profesor y tutor. Posgrado de Ciencias Cognitivas. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (UAEM). Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, desde 2010.

Profesor y tutor. Licenciatura en Neurociencias. Facultad de Medicina, UNAM, Ciudad de México, desde 2019.

-

Psicobiología

Neurociencia conductual y cognitiva

Conciencia

Filosofía de las Ciencias Cognitivas

Epistemología del problema mente-cuerpo

-

American Society for Neurochemistry

Society for Neuroscience (hasta 1979)

International Society for Neurochemistry

Sociedad Mexicana de Ciencias Fisiológicas

Sociedad Mexicana de Psiquiatría Biológica

Sociedad Mexicana de Neurología y Psiquiatría

Asociación Mexicana de Epistemología

Sociedad Mexicana de Primatología

American Association for the Advancement of Science

New York Academy of Sciences

Sociedad Colombiana de Psiquiatría Biológica

Miembro numerario (silla VI) Academia Mexicana de la Lengua

Socio Honorario. Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana

Académico Correspondiente en México, Real Academia Española

-

Desde 2001. Seminario de Problemas Científicos y Filosóficos, UNAM (SPCyF). Director del Seminario: Dr. Ruy Pérez Tamayo, hasta 2015.

Desde 2010. Seminario Multidisciplinario de Música y Mente, UNAM (S3M). Directores del Seminario: José Luis Díaz y Enrique O. Flores.

Desde 2012. Miembro del Programa Universitario de Bioética, UNAM.

Desde 2016. Coordinador del grupo de Neuroética. Programa Universitario de Bioética, UNAM.

Desde 2023. Nueva época del Seminario Universitario de Problemas Científicos y Filosóficos, UNAM (SUPCyF). Director del Seminario: Dr. Ambrosio Velasco. https://www.facebook.com/SPCF.UNAM

-

1962. Diploma a la dedicación al estudio. Facultad de Medicina, UNAM,

1967. Felicitación por el examen profesional. Facultad de Medicina, UNAM,

1967-1968. Beca de la UNAM en Neurofisiología. Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas, UNAM.

1970-1972. Beca de la Foundation’s Fund for Research in Psychiatry.

1973-1975. Donativo de la Scottish Rite Schizopherenia Research Program.

1973-1978. Donativos del Centro Mexicano para Estudios en Farmacodependencia,

1976-1977. Consejo Directivo del Instituto Mexicano para el Estudio de las Plantas Medicinales, A.C. México, D.F.

1977-1979. Donativo del Centro de Integración Juvenil, México, D.F.

1982-1986. Comisión dictaminadora del Departamento de Psicofisiología, Facultad de Psicología, UNAM.

1986. Consejo Editorial. Social Pharmacology D.I.A. Journals.

1984-2006. Investigador Nacional, Sistema Nacional de Investigadores, Secretaría de Educación Pública de México.

Desde julio 1990. Programa de Estímulos a la productividad y el rendimiento de los investigadores del Subsistema de la Investigación Científica, UNAM. Nivel actual: C

1992. Who´s Who in the World, New Providence, EUA.

Desde 1992. Consejo Editorial. Ludus Vitalis.Revista de filosofía de ciencias de la vida. México, D.F.

1994-1995. Editor y miembro del Consejo Editorial. Boletín de la Sociedad Mexicana de Ciencias Fisiológicas.

1995. Consejo Editorial. Cuadernos de Cognia. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Julio 1994 – diciembre 1995. Beca sabática. Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, UNAM

1995. Complemento de beca sabática. The University of Arizona (Cognitive Science Program, Social Sciences School, The President of the University of Arizona).

1995. Participación de donativo. The McDonnell Pew Program for Cognitive Neuroscience (a través del Cognitive Science Program, The University of Arizona).

1997. Medalla y Diploma por 30 años de servicios académicos. UNAM,

Marzo 1999. Conferencia magistral “Conciencia, cerebro y psicofarmacología” Congreso de la Asociación Mexicana de Farmacología. Zacatecas.

Desde 2000. Comité editorial internacional de Salud Mental (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría, México).

Desde 1999. Miembro del Seminario de Problemas Científicos y Filosóficos, UNAM.

2003. Medalla y diploma por 35 años de servicios académicos, UNAM.

2006. Comité editorial de Perspectiva Interdisciplinaria de Música.

21 al 23 de junio de 2006. Cátedra Extraordinaria Ruy Pérez Tamayo. Universidad Veracruzana. Xalapa, Veracruz, México.

13 al 27 de enero de 2007. Coordinador del ciclo de conferencias “Quetzalcóatl, la serpiente emplumada. Historia y actualidad del mito” desarrollado en el Museo de América de Madrid.

2007. Medalla y diploma por 40 años de servicios académicos, UNAM.

19 de junio de 2007.Moderador de la Mesa Redonda “Conciencia y dolor”. Primer encuentro Iberoamericano de Investigadores en dolor. Boca del Río, Veracruz, México.

Noviembre de 2007. Moderador en el simposio Ciencias Cognitivas y Filosofía de la Mente. XIV Congreso Internacional de Filosofía. Asociación Filosófica de México. Mazatlán, Sinaloa,

2009. Artículo destacado. “El legado de Cajal en México”. Revista de Neurología (España) Vol 48, número 4.

Junio de 2009. Miembro asociado. Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría Biológica. Bogotá, Colombia.

23 de junio de 2011. Conferencia magistral de inauguración con el tema “La conciencia, enjambre del cerebro”. Congreso Regional Centro de la Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana. Puebla, Pue. México.

Octubre de 2011. Editor huésped. Sección temática sobre “Conciencia”. Ciencia (Revista de la Academia Mexicana de Ciencias).

2012. Cátedra Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. México, D.F.

2009-2012. Miembro del Seminario de Investigación en Ética y Bioética, UNAM (SIETyB). Directora del Seminario: Dra. Juliana González. www.dialogos.unam.mx

19 al 22 de marzo de 2013. VIII Coloquio Neurohumanidades: “Mente ≈ cuerpo, Diálogo multidisciplinario en el 70 aniversario de José Luis Díaz Gómez.” Facultad de Medicina, UNAM; Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñíz; Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia; Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas, UNAM y Posgrado de Ciencia Cognitivas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos.

Junio de 2012. Medalla y diploma por 45 años de servicios académicos, UNAM.

13 de junio del 2013: Elegido miembro numerario de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua para ocupar el sillón VI (Séptimo ocupante).

14 de septiembre del 2013. Nombramiento como socio honorario de la Asociación Psiquiátrica Mexicana “Por su ejemplar trayectoria profesional y académica y sus contribuciones a favor del desarrollo de la Psiquiatría y la Salud Mental.”

12 de junio del 2014. Discurso de ingreso como académico numerario a la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua. Diploma de membresía.

18 de junio de 2014. Académico Correspondiente en México, Real Academia Española. Diploma de miembro correspondiente.

2016. Miembro del jurado calificador del Premio Internacional Eulalio Ferrer en representación de la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua.

Noviembre de 2016 a Enero de 2017. Coordinador Adjunto. Coordinación Adjunta de Investigación del Foro Consultivo Científico y Tecnológico, A.C. Ciudad de México.

Julio de 2017. Miembro del Consejo Editorial. Revista de la Universidad de México.

6 de Octubre de 2017. Homenaje y reconocimiento “Por su labor de vanguardia y su sostenido apoyo en el desarrollo de las Ciencias Cognitivas, en México y más allá, como tarea verdaderamente transdisciplinar, donde confluyen ciencia, humanismo, arte y pensamiento ecológico.” Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Centro de Estudios Vicente Lombardo Toledano, Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Cognitivas, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

2020. Miembro del Comité Editorial. Mente y Cultura (Revista del Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñíz, Ciudad de México).

2021. Miembro del Consejo Académico. Instituto María Díaz de Guerra (Maldonado, Uruguay)

2022. Simposio “en reconocimiento a José Luis Díaz Gómez” sobre “Imaginarios” en el XVII Coloquio de Neurohumanidades. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñíz, martes 29 de marzo 2022.

2023. Sesión homenaje al Dr. José Luis Díaz por su 80 aniversario en el Simposio Anual de Neurohumanidades. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñíz, 15 de marzo de 2023.

2023. El número 2 del volumen 4 de la Revista Mente y Cultura (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñíz, México) fue dedicado al Dr. José Luis Díaz como homenaje por sus 80 años. Contiene algunas de las comunicaciones realizadas el 15 de marzo en ese Instituto.

2023. Integrante del Comité Asesor del Seminario Universitario de Problemas Científicos y Filosóficos de la UNAM.

Relatos de ciencia y docencia

Explore cada una de estas secciones en el menú superior-

Desde los pasillos de la UNAM hasta colaboraciones internacionales, la trayectoria del Dr. Díaz refleja una vida dedicada a desentrañar los enigmas de la mente."

-

A través de cursos, seminarios y programas de posgrado en diversas instituciones —especialmente en la UNAM—, el Dr. José Luis Díaz ha formado generaciones de pensadores y científicos. Hoy continúa guiando mentes inquietas en su curso de Neurociencia Cognitiva dentro del Posgrado en Filosofía de la Ciencia, un espacio abierto también a oyentes externos que buscan comprender la conciencia desde una perspectiva crítica y rigurosa.

-

Una prolífica colección de obras que entrelazan ciencia y reflexión, ofreciendo una ventana al complejo mundo de la conciencia y el comportamiento humano.

-

Comprometido con acercar la ciencia al público, el Dr. Díaz traduce complejos conceptos neurocientíficos en conocimientos accesibles y relevantes para todos.

-

Un homenaje a la memoria de su tío, el Dr. Manuel Díaz González, cuya vida y legado inspiran una reflexión profunda sobre la justicia, la memoria y la identidad.

Principales aportaciones

-

· Papel e hipótesis de la serotonina cerebral en las psicosis.

· Estrategia de intersección y contraste como modelo animal de psicosis.

· Efectos de dosis humanas y crónicas de LSD, anfetamina y antipsicóticos sobre el metabolismo cerebral de serotonina en la rata.

-

Clasificación psicofarmacológica con base en los usos y acciones cerebrales, conductuales y mentales de las drogas psicotrópicas, en particular de los alucinógenos y psicodislépticos naturales y sintéticos.

-

· Catálogos de sinonimia y usos de plantas medicinales mexicanas.

· Usos y efectos de plantas mágicas mexicanas poco conocidas, en especial la “hoja de la Pastora” (Salvia divinorum) de los mazatecos y la “hoja madre” (Calea zacatechichi) de los chontales.

· Taxonomía de drogas psicotrópicas y psicodislépticas.

· Métodos en etnofarmacología.

-

· Técnicas de análisis de la conducta espontánea individual y social de animales de laboratorio, incluyendo roedores, gatos y primates.

· Efectos de psicofármacos sobre la conducta libre en animales.

· Métodos en etofarmacología.

-

· Establecimiento, reproducción y estudio conductual de colonias de primates no manipulados (Macaca arctoides) en la Unidad de Investigaciones Cerebrales, Instituto Nacional de Neurología y en la Unidad de Neurociencias, Instituto Mexicano de Psiquiatría.

· Métodos de análisis de la conducta y estructura social en primates.

-

· La teoría de procesos pautados en Psicobiología, en referencia al problema mente-cuerpo y a la epistemología.

· El doble aspecto mente-cerebro.

· Historia del problema mente-cuerpo

-

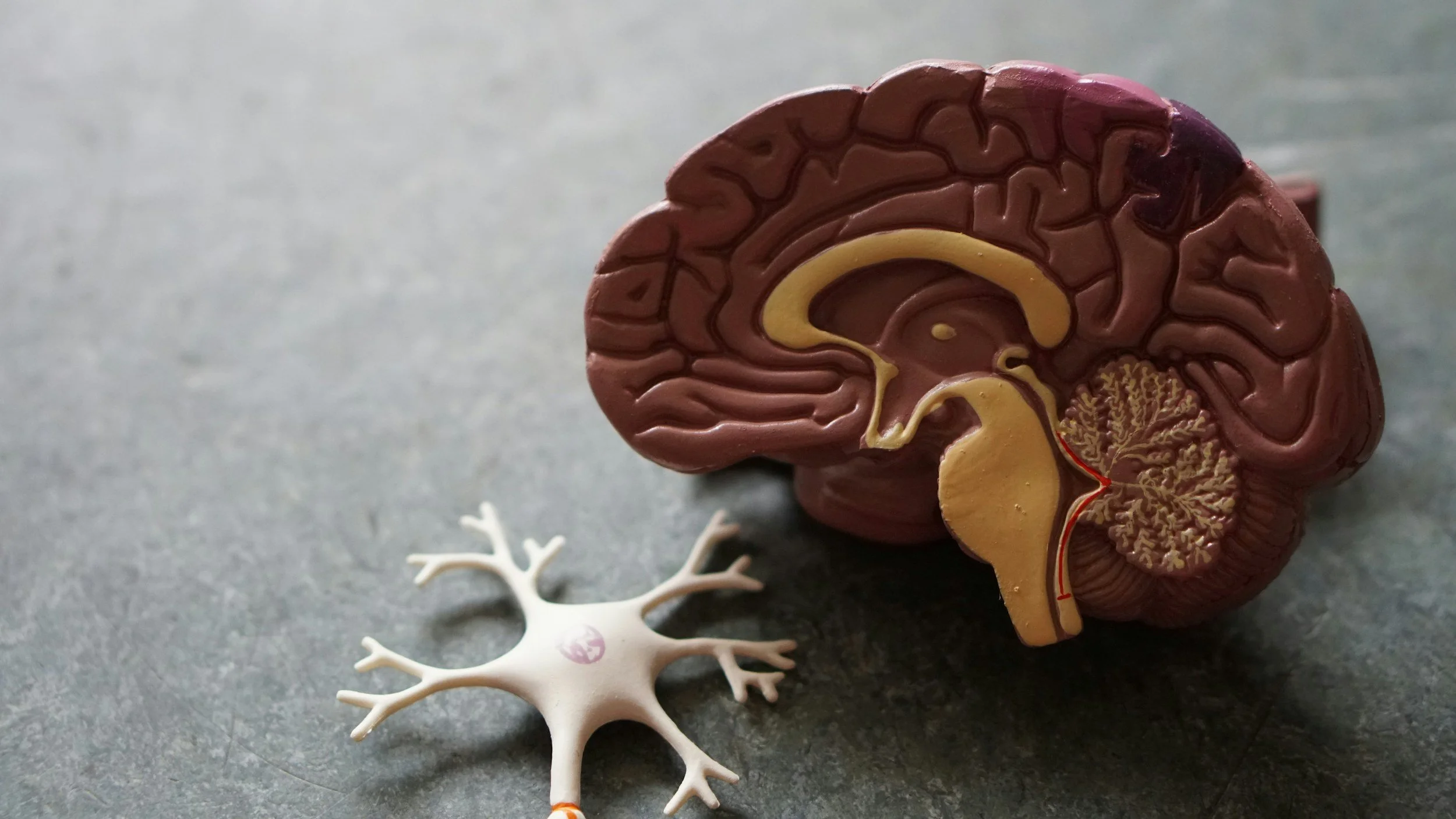

· Estructura, análisis y correlatos cerebrales de la conciencia.

· Los textos fenomenológicos como expresiones de procesamiento consciente.

· Modelo procesal de la conciencia fenomenológica.

· Hipótesis del enjambre sobre el fundamento nervioso de la conciencia.

· Los sueños en las artes como modelos de la conciencia onírica.

-

· Modelo circunflejo del sistema afectivo en base a los términos de la emoción.

· La emoción musical y el lenguaje: fundamento cerebral.

· Términos de la emoción y dimensiones afectivas

Últimas publicaciones

-

Las moradas de la mente

En esta obra, José Luis Díaz continúa con los temas planteados previamente en La conciencia viviente al presentar una visión integral del estudio del cerebro y la conciencia, y expone los elementos que dan origen e influyen en la formación de la conciencia.

-

El enredo mente - cuerpo

La amalgama de cuerpo y mente que constituye a toda persona es uno de los misterios más antiguos, recalcitrantes y trascendentes del pensamiento humano. El enigma es la naturaleza de esa unión, relación, o dilema: ¿se trata de una sola cosa o dos, una material y otra espiritual?

-

Neurofilosofía del yo

El libro define los rasgos, aspectos y expresiones de diez facetas o funciones particulares y peculiares de la autoconciencia que pueden operar por separado, coordinarse parcialmente o trabajar como un todo interactivo e integrado.

Numeralia

-

Libros, monografías 18

Libros editados, compilaciones 10

Artículos y capítulos de investigación 95

Capítulos en libros 72

Artículos de revisión y textos didácticos 73

Total de artículos científicos 268

Artículos literarios 3

Artículos periodísticos de comentario y divulgación 225

Traducciones 3

-

Congresos y resúmenes internacionales 53

Congresos y resúmenes nacionales 99

-

Tesis dirigidas de licenciatura 11

Tesis dirigidas de maestría 8

Tesis dirigidas de doctorado 4

Comités tutorales (desde 2008) 14

-

Nacionales (desde 2002) 164

Internacionales (desde 2005) 53

Curso

Neurociencia Cognitiva: Las facultades mentales

A lo largo de 14 sesiones, el curso aborda temas como la sensación, percepción, emoción, pensamiento, lenguaje, imaginación, memoria, intención, conducta social, atención y conciencia. Cada tema se examina desde múltiples dimensiones: definiciones y conceptos, modelos funcionales, fenomenología, métodos de análisis, fundamentos neurobiológicos y psicopatología asociada.

El curso está diseñado para estudiantes de posgrado y oyentes interesados en comprender la mente humana desde una perspectiva interdisciplinaria. Se apoya en textos fundamentales como The New Cognitive Neurosciences de Gazzaniga et al., y Principles of Neural Science de Kandel et al., así como en artículos del propio Dr. Díaz.

En la página dedicada a su ingreso a la Academia Mexicana de la Lengua, el Dr. José Luis Díaz presenta su discurso titulado La naturaleza de la lengua, en el cual explora el lenguaje humano desde una perspectiva interdisciplinaria que abarca la neurociencia, la biología evolutiva y la filosofía. En este discurso, analiza cómo la lengua se manifiesta no solo en palabras, sino también en gestos, aromas, música y otras formas de comunicación, destacando su origen evolutivo y su base neurobiológica. Además, reflexiona sobre la relación entre lenguaje y pensamiento, proponiendo que la comprensión del lenguaje requiere considerar tanto su dimensión simbólica como su contexto social y cultural. Este enfoque integrador resalta la importancia de la lengua como una manifestación compleja de la mente humana y sugiere que su estudio debe abarcar múltiples disciplinas para comprender plenamente su naturaleza y significado.

El tío Manolo

Este espacio rinde homenaje a la memoria del Dr. Manuel Díaz González, tío del autor, médico del municipio de Incio (Lugo, España), republicano convencido, editor de una revista política y cultural, y víctima de la represión fascista al inicio de la Guerra Civil Española. Su vida —interrumpida sin juicio ni causa la tarde del 11 de septiembre de 1936— sigue siendo un faro de reflexión sobre la justicia, la memoria y la identidad. Aquí se reúnen las publicaciones de José Luis Díaz Gómez dedicadas a reconstruir su historia, su tiempo y su legado, con la convicción de que recordar es también resistir.

Contacto

Departamento de Historia y Filosofía de la Medicina, Facultad de Medicina.

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM.

Dirección: Brasil y Venezuela, Centro Histórico, México D.F.